Pols: Congestion Pricing Will Hurt Small Biz

BY BENJAMIN FANG

As a congestion pricing proposal gains footing in Albany, a coalition of Queens elected officials, civic groups and business leaders is continuing to voice opposition.

Last month, the group spoke out against what they deem as a toll on the four free East River crossings: the Ed Koch Queensboro Bridge, Brooklyn Bridge, Manhattan Bridge and Williamsburg Bridge.

If passed in the budget, the congestion pricing plan would charge private vehicles and trucks entering the core business district in Manhattan south of 60th Street. The proposal would generate more than $1 billion annually to fund subway improvements for the MTA.

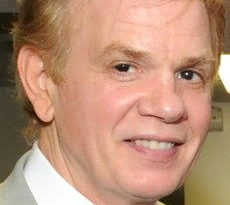

Assemblyman David Weprin, an outspoken critic of congestion pricing, argued that his eastern Queens district doesn’t have accessible public transportation, so many residents rely on their cars to get to Manhattan.

“It is an expensive option already, and if this congestion tax is imposed, it will be a large burden on middle-class homeowners,” he said, “as well as small businesses that rely on the free bridges now for multiple deliveries.”

Weprin noted that the four bridges have remained free for more than a century, and believes they should stay a free option. Travelers still have the option of taking one of the city’s tolled bridges, such as the Queens Midtown Tunnel, which are often quicker, he said.

“We believe in consumer choice,” he said.

There are also many people with disabilities and seniors who can’t take mass transit, the assemblyman said, and need their cars for medical appointments, employment or to visit family members.

Rather than congestion pricing, Weprin recommended bringing back a commuter tax on people who live in New Jersey, Connecticut and the suburbs, but work in New York City. He argued that they benefit from police, sanitation and transportation services, but don’t pay their fair share.

If marijuana is legalized in the state next year, which Governor Andrew Cuomo announced he would attempt, Weprin said he would consider taxing the industry to help fund the MTA’s capital needs as well.

“This is, by all standards, the worst regressive tax,” Weprin said. “It shouldn’t be done on the backs of middle-class people who have no other choice than to drive into Manhattan.”

Councilman Barry Grodenchik said he was skeptical of the MTA, both in their ability to rein in overspending on projects and their promise to expand the system to reach his eastern Queens district.

When the councilman proposed an expansion of buses or rail service to Belmont Park, the MTA immediately rejected the idea, he said.

He has even circulated a letter to his colleagues, asking the MTA to include the entire borough of Queens on the subway map. Right now, it’s “out of sight, out of mind,” Grodenchik said.

He also cast doubt as to whether congestion pricing would actually solve the congestion problem. Cars in the core area of Manhattan travel at an average speed of 4.7 miles per hour, and if passed, congestion pricing would only increase speeds by 9 percent, or 0.43 miles per hour.

“You can, at a brisk walk, walk faster than that,” he said.

Councilman I. Daneek Miller, who represents the neighborhoods of southeast Queens, said the congestion pricing plan doesn’t address the transit needs of his district, which is an “extreme transportation desert.”

While other neighborhoods are getting ferry service, potential trolley service and other improvements, southeast Queens, which has among the longest travel times into Manhattan, gets nothing, he said.

“We have no options, yet we are the ones being asked to pay,” Miller said. “The burden continues to be on the people who suffer most.”

He was also skeptical of giving more money to an agency that “has proven itself not to be worthy of it.”

“There needs to be some level of performance that would justify any additional money going in,” he said.

Weprin added that the governor pushed for a congestion pricing proposal last budget session, but faced “overwhelming opposition” by Assembly Democrats.

“I’m hoping that will stay together,” Weprin said. “There’s got to be better proposals.”

Last week, six state senators who joined the Democratic majority announced their support for congestion pricing, including Jessica Ramos from Queens and Andrew Gounardes, Zellnor Myrie and Julia Salazar from Brooklyn.

In a joint statement, they said they intend to deliver on their promises of bringing the MTA and its infrastructure into the modern era.

“Congestion pricing will offer them less crowded streets and offer the overwhelming majority of transit riders new signals, subway cars and hundreds of station elevators,” the statement read. “Without it, we will not achieve the revenue necessary to achieve these goals.”

The newly elected representatives pledged to hold the MTA accountable, watching closely how funds are spent in the best interest of riders.

“We must reach deep into subway deserts and suburban areas where commutes can be especially long and unreliable,” they added. “The task before us is a big one, but completing it is central to restoring trust in government and cementing the economic future for all New Yorkers.”